you are here: @digidem encodes story into a map

The scene appeared normal: a small house by a pond, with occasional traffic passing, mostly trucks and laborers from the work site up the road. But Gregor MacLennan was focused on the out of place details. “A sheen of oil floating on the top” of the pond, he recalls, “the gas flare roaring over the trees, and the only source of water trickling out of the hillside with the smell of crude.”

MacLennan, the coder behind Digital Democracy’s new ClearWater map, did not start out as a techie. As an environmental activist, he has spent more than ten years working in the Amazon Basin, studying the harmful effects of contamination from oil driling.

But two years ago, standing outside the home of Guillermo Grefa and Lydia Aguinda in Ecuador’s Rumipamba region, he was disturbed by how hard it would be to describe the scene to anyone else. “I knew more about the region than most other people,” he says, “but it was still very different to see it in reality.”

MacLennan and Digital Democracy founder Emily Jacobi are creating ways to bridge that difference, the one between knowing that oil drilling affects local communities and seeing the reality of that impact, in damage to land, homes and lives.

The map tool, launched in April, showcases ClearWater’s efforts to build collection systems for contamination-free rainwater. It is groundbreaking for the way it smoothly combines data gathering, mapping and storytelling.

Where many maps give context in clickable popups, this one includes a “larger story” on the left side that updates as you move around the map. And this larger story, compiled by ClearWater and Digital Democracy, presents a well-planned path through the map, shifting the map location as you read the narrative.

By balancing user choice and structured storytelling, the map resolves a constant tension in digital advocacy, whether to drive viewers along one path through one story–like a video or a “tour”–or to hand viewers the steering wheel, by providing multiple options and allowing each user to customize the experience for the greatest relevance.

Digital Democracy, a member of our #TABridge network, seeks to democratize the ability to advocate online, as the name implies. “Across the board,” says Jacobi, “we’re working on tools and workflows that allow partners to share their versions of the truth directly, in ways that empower them as leaders on pressing human rights and environmental issues.” This is the central premise behind their Remote Access project.

Alex Goff, the international field coordinator for ClearWater, says he hopes the new map can give indigenous groups in Ecuador “a platform to highlight threats to their territory, demonstrate the importance the land holds for them by presenting land use, areas of cultural and ancestral importance, and conservation efforts to a global audience … on their own terms.”

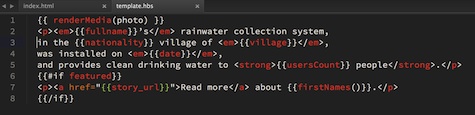

The map is designed for ease of input as well as usage. MacLennan says contributors in remote areas can complete a new entry themselves by updating one Google spreadsheet. The tool does the rest, placing locations, statistics, even photos, into the proper sections of the site. The snippet of code below shows a particularly elegant example of MacLennan’s approach: Using data points entered as cells in the spreadsheet, the map tool inserts the data into easy-to-read blocks of prose about the location, effects and individuals responsible for each source of clean rainwater in the map area. The data is the story, and vice versa.

Of course, challenges remain to widespread adoption by indigenous groups, says Goff, including “training people to use tools that are very new to them, adapting to a technological world that, while forced upon them from the outside, they will need to in order to defend their rights and lands.”

ClearWater is working to broaden local usage of the tool with a community-centric training program. “Right now,” says Goff, “there are students from each of the five nationalities ClearWater works with taking a GIS mapping course.” He says the students will then return to their indigenous communities, to deploy these new mapping skills. (This train-and-return approach is used regularly by #TABridge participant Accountability Initiative.)

Another challenge MacLennan hopes to resolve is the fact that setting up the tool for the first time still requires some web coding. “I want to make it possible to create your own map without any programming” in future versions, he says, “and add the ability to edit in the map itself, rather than using the spreadsheet, which is still a technical barrier to some people.”

Digital Democracy and ClearWater both emphasize the need to lower the barriers for using digital tools. Jacobi says a vital step to help marginalized groups is “reducing their dependence on outside ‘experts,’ allowing them to directly gather, manage and disseminate information.”

“The communities themselves must be the leaders,” says Goff. “Sustainability hinges upon local capacity, not a top-down model that claims, ‘we know what’s best for you.'”

For MacLennan, the power to tell a story may be the most important resource the pilot system offers. “We can never bring everyone to the Amazon, but the hope is that maps can give a geographical context to the story. … These were families, mothers, children, trying to live a healthy life. We needed to tell that human story together with the ‘data’ story.'”