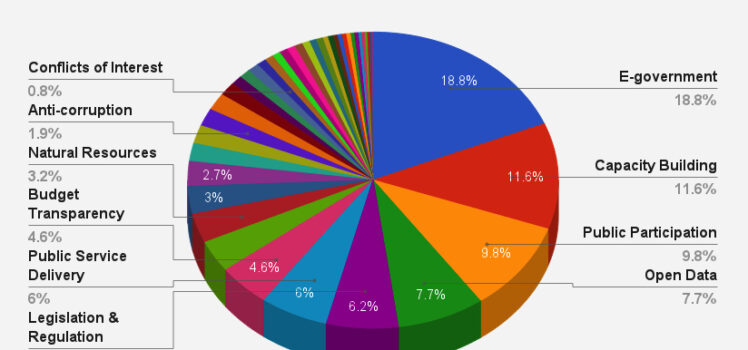

On the eve of this week’s Open Government Partnership summit in Latin America, the OGP has released new data compiling every commitment made by countries for the 2014-2016 OGP cycle. The Support Unit of OGP went through almost 900 new commitments in the national action plans of 49 countries and categorized them by “thematic tags,” as Abhinav Bahl of OGP explains.

Many governments are now publicly releasing swaths of new data each month. A growing number of private companies are doing the same, notwithstanding tensions over issues likemandatory disclosure and privacy. Used well, this windfall of raw material can do much to inform policymaking and public debate. But it can do even more—if it can be combined with information from other sources, including crowdsourcing, to improve how government regulates. The practical challenge, however, is that far too much valuable data still sits in silos, gathering dust, unavailable and unhelpful even to the regulators who collect it.

Imagine, for instance, if an inspector at an environmental agency had ready access to data on a company’s compliance with regulatory rules—on clean water, air, and chemical disposal, for example—from across her agency. Imagine if she also had access to data from other agencies about corporate compliance with workplace safety and financial regulatory rules? She could then plan her regional inspections to increase the chance of discovering bad corporate behavior. At the very least, it is worth finding out if access to better systematic data about the companies government regulates and their compliance with laws and regulations could improve the effectiveness and efficiency of regulation.

After weeks of consultation—and a “blink-and-you’ll-miss-it” public comment period—a group of expert advisors to the UN has issued a report on the “data revolution” for sustainable development.

“A World That Counts,” released in final draft on November 6, was prepared for the Secretary General’s office amid planning for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agenda launching in 2015, and an urgent need for data and information to support the SDG process.

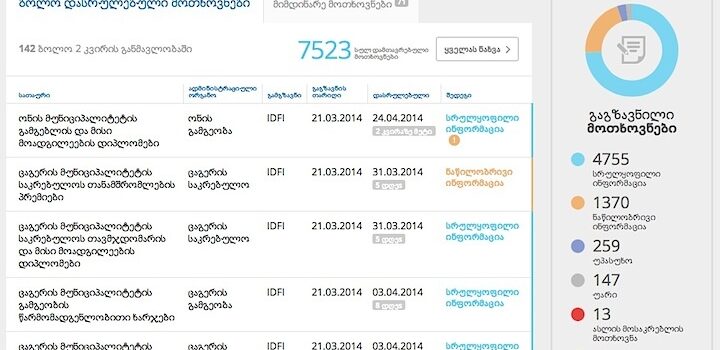

The nation of Georgia has steered continually toward more open government since its 2012 elections, but local NGOs remain ahead of leaders in promoting reform.

The country reached a watershed this fall, when the international Open Government Partnership (OGP) appointed Georgia to its steering committeee and approved Georgia’s second OGP action plan. The government set new goals for itself in transparency of political contributions and surveillance activities, and extended prior plans for online data publishing and citizen-friendly web tools.

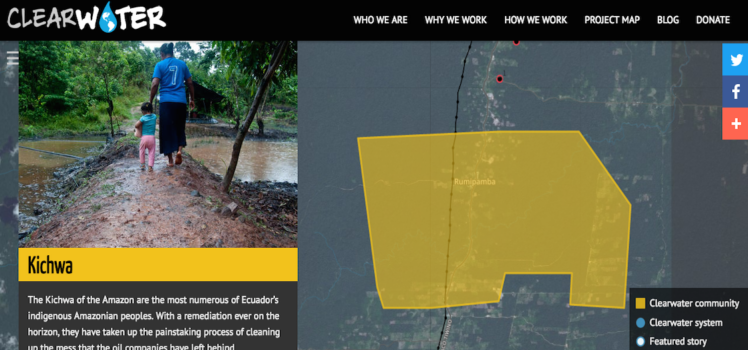

The scene appeared normal: a small house by a pond, with occasional traffic passing, mostly trucks and laborers from the work site up the road. But Gregor MacLennan was focused on the out of place details. "A sheen of oil floating on the top" of the pond, he recalls, "the gas flare roaring over the trees, and the only source of water trickling out of the hillside with the smell of crude."

MacLennan, the coder behind Digital Democracy's new ClearWater map, did not start out as a techie. As an environmental activist, he has spent more than ten years working in the Amazon Basin, studying the harmful effects of contamination from oil driling.