Amid the flipbook churn of links from Twitter, Facebook and email yesterday, I saw two that brought different sides of me into sharp contrast.

One was a picture based on the tumblr The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows. The Dictionary is the brainchild of graphic designer and editor John Koenig. Koenig imagines new words for feelings that should have their own word but don't, like the momentary terror when your eyes haven't adjusted to the dark yet, or the wish that someone else's phone buzzing had been yours (those two are mine). Buzzfeed's Daniel Dalton did a really nice job illustrating some of Koenig's words a few weeks ago, which may explain why the list is showing up in my feeds a lot.

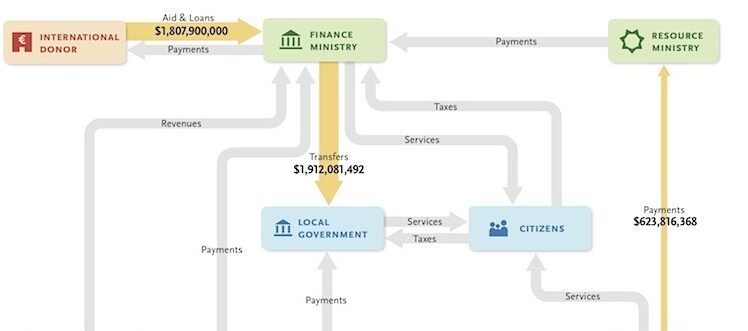

When we present data and information, the medium is often the message. “Download our full dataset (19MB),” sends a different message than “New figures suggest the oil spill would cover Lake Erie.” The tension between data depth and clear narratives is not a simple one, though. Sometimes the most important story data tells is in the relationships between data sets.

In the oil, gas and mining sector, a complex web of relationships governs the flow of money from private companies to governments to the local communities that benefit from government spending and services. Groups like Publish What You Pay and NRGI are in Ottawa discussing better tools to promote accountability in the extractive industries by extracting data on these fiscal flows, which can also include foreign aid and local taxes, among other things.

The World Bank has been working with colleagues from these fields to draft a tool that can illustrate the web of relationships in the extractive sector, and serve as a visual backdrop for posting data in context.

This week, the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) is hosting extractives experts from six countries to at the International Open Data Conference (IODC) in Ottawa, Canada.

Civil society actors and government officials from Ghana, Indonesia, Mexico, Mongolia, the Philippines and Tanzania arrived ahead of the IODC event for an intensive workshop on the power of open data to enhance their efforts in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI).

The workshop marked the inauguration of our Extractives Open Data Leaders program, established to strengthen open data work within EITI country processes by improving data availability, increasing data standardization, improving open data licensing, and enhancing data reuse.

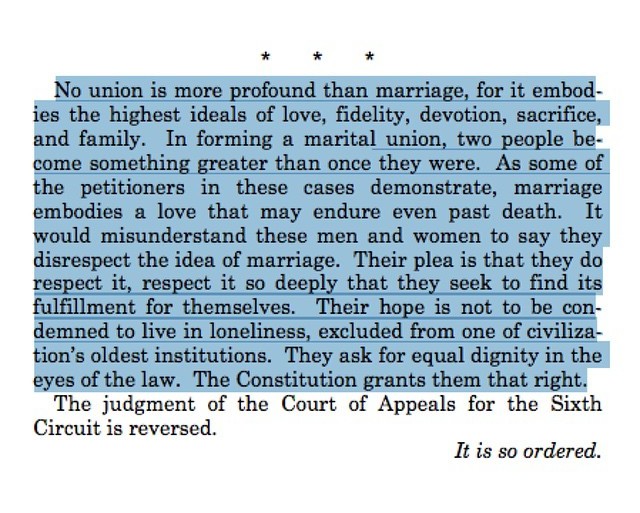

Proud to be quoted in this thoughtful piece by non-profit advisor Gina Schmeling, originally posted at Darim Online.

Transparency itself isn’t a new concept. In the US for example, nonprofits must publicly file 990s annually. This ensures accountability, and is a requisite for tax-exempt status. But transparency does not begin and end with financial information. There are new dimensions, new imperatives emerging from technology, and perhaps most profoundly, transparency is now a critical leadership skill. That feels pretty new to many of us.

But today’s leaders need to understand that transparency is no longer optional. When the rules of the game have changed, leaders necessarily need to adapt their approaches. What roles does transparency play here? According to Charlene Li, author of Open Leadership, “transparency is not defined by you as a leader, but by the people you want to trust you and your organization. How much information do they need in order to follow you, trust you with their money or business?” (pg. 193). It’s all about trust -- and trust (and its corollary, attention) are the currency of our current attention economy.